A lifetime measured in kilowatts

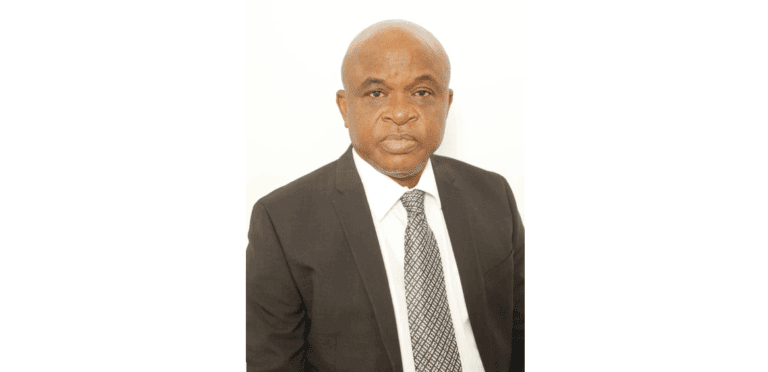

William Amuna, Board Chairman of the Electricity Company of Ghana, reflects on a career spanning nearly four decades and the challenges facing the power industry today

There was no power grid north of Kumasi when William Amuna was a young engineer fresh out of university. In the mid-1980s, only three out of 10 Ghanaians had access to electricity. Extending that grid, and connecting more and more people to mains power, became Amuna’s lifelong mission.

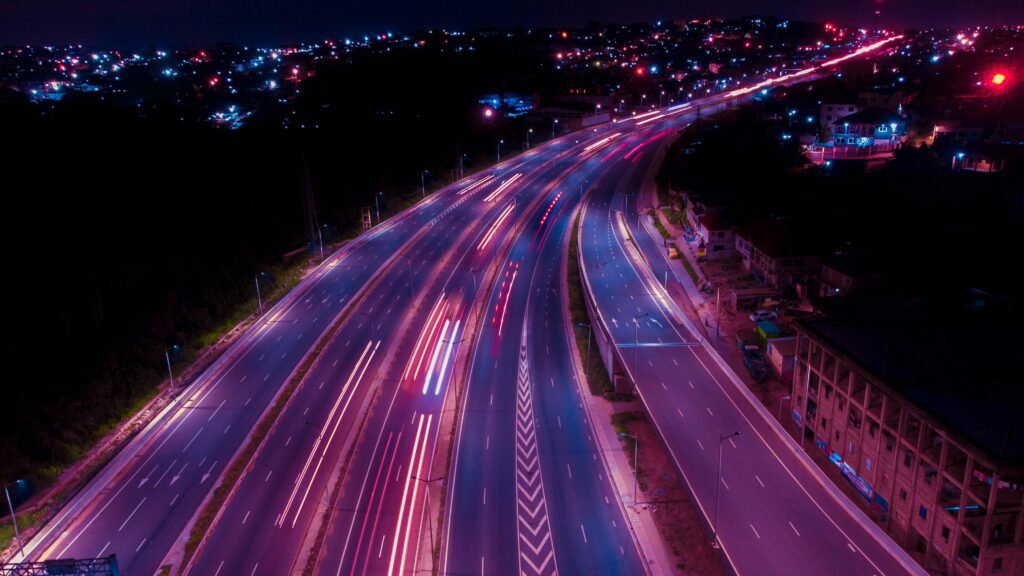

Over the course of his near 40-year career in the power industry, Ghana’s population has more than doubled to 34 million and power capacity quadrupled to 4 GW. Today, Ghana is within a whisker of delivering universal access to electricity – one of the first countries in sub-Saharan Africa to do so – while interconnectors with neighbouring countries allow Ghana to trade power with the 12 nations of the West African Power Pool.

Ghana’s success is clearly an example for other countries to follow, even though its power sector is not without its challenges. Amuna, who was recently appointed Board Chairman of the state-owned power distributor Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG), says his priority is to put the company on a sounder financial footing by reducing the incidence of theft and technical losses from the distribution system. He hopes that this, and the installation of new digital meters, including pre-paid meters, will increase revenues that will help ECG repay the $1.73 billion it owes independent power producers (IPPs).

No electricity, no votes

Amuna joined the Volta River Authority (VRA), Ghana’s leading electricity generator and supplier, soon after university. One of his first jobs was to oversee the extension of the national grid to the country’s northern regions. The grid stopped at Kumasi, and north of that, stretching for hundreds of kilometres, was about two-thirds of the country.

He describes the exhilaration he felt as town after town lit up as the grid advanced. To extend electricity from district capitals to surrounding towns, the government introduced the Self-Help Electrification Programme (SHEP), by which communities and the government shared the cost of electricity access.

“To qualify, communities had to organise themselves and contribute some materials, like electricity poles, and the government would come in with transformers, wires and cables to connect the town to the grid,” Amuna recalls. “It became a kind of competition. Towns vied with each other to be on the SHEP scheme.” Then it became political. In Ghana’s highly competitive democracy, towns put up signs that read: “No electricity, no vote”. As a result, says Amuna, the national electrification programme remained a priority no matter which political party was in power.

Strengthening the grid

Amuna rose to become director of technical services at the VRA. In 2013, he was appointed CEO of the Ghana Grid Company (GRIDCo) responsible for the operation of the National Interconnected Transmission System (NITS). The company had been part of the VRA until electricity reforms in 2006 established separate entities for power generation, transmission and distribution. As CEO, Amuna focused on improving the resilience of the grid, gradually upgrading the transmission network to 330 kV to reduce the incidence of blackouts. He also worked to reinforce interconnectors to the West African Power Pool, which has allowed Ghana to be a net exporter of electricity.

Amuna says private companies have also played an important role in these efforts – both as independent power producers (IPPs) and in public-private partnerships to extend the grid. Mining companies, for example, have built transmission lines and substations to their sites under an agreement with GRIDCo, the operator, which allows mines to recoup their investment with lower tariffs.

“The government has many competing priorities, so the involvement of IPPs, mining companies and other industries in the electricity sector is an excellent thing,” says Amuna.

In 2017, Amuna stepped down as CEO of GRIDCo to become senior advisor to the Minister of Energy. His next role was as Technical Coordinator at the Millennium Development Authority (MiDA), responsible for delivering the $315 million, US-funded Ghana Power Compact aimed at stemming technical losses in the transmission system. “We built two of the largest substations in Ghana,” Amuna says. It was a huge stride in delivering a more stable system.

Financial stability

Since May 2025, Amuna has been Board Chairman of the ECG, which distributes power to the populous southern provinces. He says his main priority will be to reinforce the distribution network, parts of which are now very old. But to pay for it, he first needs to raise revenues. He plans to go about this by “digitalising everything”. “We will install pre-payment meters in households, and we will take metering systems out of the premises of industrial plants, so they cannot be tampered with. Once we’ve increased revenues in this way, we will be able to invest in upgrading and making the system more stable,” Amuna explains.

After almost 40 years in the power industry, Amuna says the future is brighter than ever. Ghana is diversifying its power supply and integrating solar and hydro production, for example, by installing floating solar panels on the Bui reservoir – a first for West Africa. The West African Power Pool is contributing to grid stability and Amuna sees it as an opportunity to transform Ghana into a major power exporter in the region.

Amuna is also looking forward to the Africa Energy Forum (AEF) in Cape Town. “It’s the best forum in the electricity business, where some people can learn from me and I also learn from many, many people. I always come back with new ideas that I can apply here,” he says.